Author: Vincenzo Piemonte, Associate Professor, University UCBM – Rome (Italy)

1.Theme description

The purpose of a solar refinery is to enable an energy transition from today’s ‘fossil fuel economy’ with its associated risks of climate change caused by CO2 emissions, to a new and sustainable ‘carbon dioxide economy’ that instead uses the CO2 as a C1 feedstock, together with H2O and sunlight, for making solar fuels.

Figure 1 – Scheme of a ‘solar refinery’ for making fuels and chemicals from CO2, H2O and sunlight[1]

On an industrial scale, one can visualize a solar refinery (see Figure 1) that converts readily available sources of carbon and hydrogen, in the form of CO2 and water, to useful fuels, such as methanol, using energy sourced from a solar utility. The solar utility, optimized to collect and concentrate solar energy and/or convert solar energy to electricity or heat, can be used to drive the electrocatalytic, photoelectrochemical (PEC), or thermochemical reactions needed for conversion processes. For example, electricity provided by PV cells can be used to generate hydrogen electrochemically from water via an electrocatalytic cell.

However, hydrogen lacks volumetric energy density and cannot be easily stored and distributed like hydrocarbon fuels. Therefore, rather than utilizing solar-generated hydrogen directly and primarily as a fuel, its utility is much greater at least in the short to intermediate term as an onsite fuel for converting CO2 to CH4 or for generating syngas, heat, or electricity. Reacting CO2 with hydrogen not only provides an effective means for storing CO2 (in methane, for example), it also produces a fuel that is much easier to store, distribute, and utilize within the existing energy supply infrastructure.

The idea of converting CO2 to useful hydrocarbon fuels by harnessing solar energy is attractive in concept. However, significant reductions in CO2 capture costs and significant improvements in the efficiency with which solar energy is used to drive chemical conversions must be achieved to make the solar refinery a reality.

Figure 2 – Schematic diagram of integrated PV-Hydrogen utility energy system

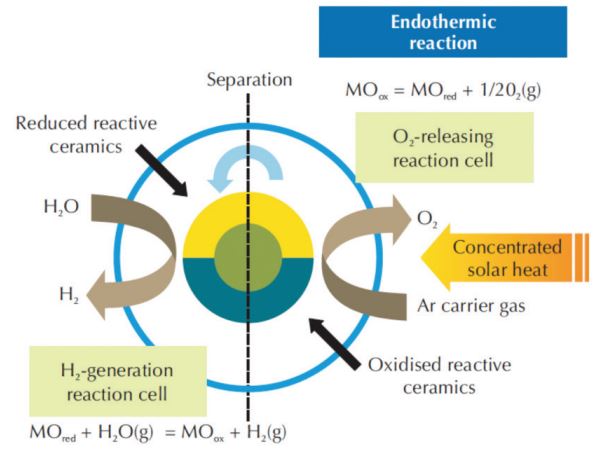

Solar energy collected and concentrated within a solar utility can be harnessed in different ways: (1) PV systems could convert sunlight into electricity, which in turn, could be used to drive electrochemical cells that decompose inert chemical species such as H2O or CO2 into useful fuels (see figure 2); (2) PEC or photocatalytic systems could be designed wherein electrochemical decomposition reactions are driven directly by light, without the need to separately generate electricity; and (3) photothermal systems could be used either to heat working fluids or help drive desired chemical reactions such as those connected with thermolysis, thermochemical cycles, etc. (see Figure 3). Each of these approaches can be used to generate environmentally friendly solar fuels that offer “efficient production, sufficient energy density, and flexible conversion into heat, electrical, or mechanical energy”[2]. The energy stored in the chemical bonds of a solar fuel could be released via reaction with an oxidizer, typically air, either electrochemically (e.g., in fuel cells) or by combustion, as is usually the case with fossil fuels. Of the three approaches listed here, only the first (PV and electrolysis cells) can rely on infrastructure that is already installed today at a scale that would have the potential to significantly affect current energy needs. In fact, the PEC and photothermal approaches, though they hold promise for achieving simplified assembly and/or high energy conversion efficiencies, require considerable development before moving from the laboratory into pilot-scale and commercially viable assemblies.

Figure 3 – Solar-Driven, Two-Step Water Splitting to Form Hydrogen Based on Reduction/Oxidation Reactions

2.Carbon Dioxide-derived fuels

The CO2 concentrations in the atmosphere are still low enough (0.04%) that it would be impractically expensive to capture and purify CO2 from the atmosphere, but other sources of CO2 are available that are considerably more concentrated. Power generation based on natural gas or coal combustion is responsible for the major fraction of global CO2 emissions, with other important sources being represented by the cement, metals, oil refinery, and petrochemical industries[3]. Indeed, a growing number of large-scale power plant carbon dioxide capture and storage (CSS) projects are either operating, under construction, or in the planning stage, some of them involving facilities as large as 1,200 MW capacity[4]. While solar PV energy conversion has the potential to reduce CO2 emissions by serving as an alternative means of generating electricity, harnessing solar energy to convert the CO2 generated by other sources into useful fuels and chemicals that can be readily integrated into existing storage and distribution systems would move us considerably closer to achieving a carbon-neutral energy environment.

Herron et al.[5], in a very recent review, examine the main routes for CO2 capture from stationary sources with high CO2 concentrations derived from post-combustion, precombustion, and oxy-combustion processes.

In post-combustion, flue gases formed by combustion of fossil fuels in air lead to gas streams with 3%–20% CO2 in nitrogen, oxygen, and water. Other processes that produce even higher CO2 concentrations include pre-combustion in which CO2 is generated at concentrations of 15%–40% at elevated pressure (15–40 bar) during H2 enrichment of syngas via a water–gas shift reaction (WGS — see Figure 1) and oxy-combustion in which fuel is combusted in a mixture of O2 and CO2 rather than air, leading to a product with 75%–80% CO2. CO2 capture can be achieved by absorption using liquid solvents (wet-scrubbing) or solid adsorbents.

In the former approach, physical solvents (e.g., methanol) are preferred for concentrated CO2 streams with high CO2 partial pressures, while chemical solvents (e.g., monoethanolamine -MEA) are useful in low-pressure streams.

Energy costs for MEA wet-scrubbing are reportedly as low as 0.37–0.51 MWh/ton CO2 with a loading capacity of 0.40 kg CO2 per kg MEA. Disadvantages of this process are the high energy cost for regenerating solvent, the cost to compress captured CO2 for transport and storage, and the low degradation temperature of MEA. Alternatives include membrane and cryogenic separation. With membranes there is an inverse correlation between selectivity and permeability, so one must optimize between purity and separation rate.

Cryogenic separation ensures high purity at the expense of low yield and higher cost. Currently, MEA absorption is industrially practiced, but is limited in scale: 320–800 metric tons CO2/day (versus a CO2 generation rate of 12,000 metric tons per day for a 500 MW power plant). Scale-up would be required to satisfy the needs of a solar refinery.

Alternatives, such as membranes, have relatively low capital costs, but require high partial pressures of CO2 and a costly compression step to achieve high selectivity and rates of separation.

A very important point to consider about solar refinery reliability is that since carbon capture reduces the efficiency of power generation, power plants with carbon capture will produce more CO2 emissions (per MWh) than a power plant that does not capture CO2. Therefore, the cost of transportation fuel produced with the aid of CO2 capture must also cover the incremental cost of the extra CO2 capture[6]. These costs must then be compared to the alternative costs associated with large-scale CO2 sequestration. Finally, one also needs to consider the longer-term rationale for converting CO2 to liquid fuels once fossil-fuel power plants cease to be major sources of CO2. Closed-cycle fuel combustion and capture of CO2 from, e.g., vehicle tailpipes, presents a considerably greater technical and cost challenge than capture from concentrated stationary sources.

3.Challenges & Opportunities

Christos Maravelias and colleagues from the University of Wisconsin have recently modeled and analyzed the energy and economic cost of every step and each alternative technology contained in a solar refinery[7]. The result is a general framework that will allow scientists and engineers to evaluate how various improvements in materials’ manufacturing and processing technologies that enable carbon dioxide capture and conversion to fuels using solar, thermal and electrical energy inputs would accelerate the development, influence the cost and impact the vision of the solar refinery. It will also enable evaluation of which alternative technologies are the most economically feasible and should be targeted or highlight those that even if developed would still be hopelessly uneconomic and can therefore be ruled out immediately.

The view that emerges from this techno-economic evaluation of building and operating a solar refinery is one of guarded optimism. On the subject of energy efficiency, it is clear that solar powered CO2 reduction is currently lagging far behind that of solar driven H2O splitting and more research is needed to improve the activity of photocatalysts and the efficacy of photoreactors. In the indirect process of transforming CO2/H2O to fuels, it is apparent that if the currently achievable solar H2O-to-H2 conversion (>10%) can be matched by solar CO2/H2-to-fuel conversion efficiencies, through creative catalyst design and reactor engineering, this would represent a promising step towards an energetically viable solar refinery. For the process that can directly transform CO2/H2O to fuels, improvements in conversion rates and product selectivity are key requirements for achieving energy efficiency in the solar refinery.

Economic efficiency is also a key to the success of the solar refinery of the future. For currently achievable CO2 reduction rates and efficiencies, the minimum selling price of methanol, a representative fuel, was evaluated by the techno-economic analysis and turned out to be more than three times greater than the industrial selling price analysis, even though the cost of the CO2 reduction step, which is estimated to be quite costly, was not included in the estimates. Improvement in the activity of CO2 reduction photocatalysts by several orders of magnitude would have a significant impact on the energy and economic costs of operating a solar refinery.

It is clear that the cost and energy efficiency of carbon capture and storage is an area where big improvements need to be made if the solar refinery is to be a success. One other point that is worth highlighting is the availability of water, since in some parts of the world the availability of water could be a big problem to face up.

To conclude, multidisciplinary teams of materials chemists, materials scientists, and materials engineers across the globe believe in the dream of the solar refinery and a sustainable CO2 based economy. Anyway it is clear that developing models to evaluate the energy efficiency and economic feasibility of the solar refinery, and at the same time identifying hurdles which have to be surmounted in order to realize the competitive processing of solar fuels, will continue to play a crucial role in the development of the required technologies.